Getting Malicious Office Documents to Fire with Protected View Enabled

Intro

I wanted to share an interesting behavior I discovered with Microsoft Office documents using a fully patched Windows 10 operating system and an up-to-date local installation of MS Office 365. I’ve been doing a lot of development work on my phishing tool lately, PhishAPI, and more or less stumbled across this new technique. I have reported it to Microsoft.

I’m writing this blog post in order to hopefully shed some light on the risk this issue introduces and to assist with white-hat phishing techniques. Most savvy users know better than to enable “Protected View” mode when opening their remote Office documents. However, doing so on a malicious document (maldoc) can result in captured information such as an IP address, action timestamps, OS/Office version disclosures, and perhaps the biggest, NTLMv2 hash leaks!

Some Background

The technique of embedding invisible HTTP and UNC calls in Microsoft Office documents is not a new one and has been around for some time now. As most of you probably know already, newer Office files such as Word documents (docx) are essentially compressed archives themselves with XML data within them. To see this for yourself, simply open a docx file in your favorite archive tool or rename to .zip and open it directly to see the contents.

Within these archives are resources such as images embedded within the Word document, as well as XML files which reference their locations. You can use external images as well, which is where HTTP calls come in. Referencing an external URI instead of a physical path within the document itself will result in Word happily calling out to retrieve it over the Internet. You can make this an invisible image so it’s not seen in the document viewer itself. A quick and easy technique used by red teams is to set up a Netcat/Python/NodeJS listener to wait for the call, something like `nc -lv 0.0.0.0 80`or `python -m SimpleHTTPServer 80`. With some basic logging, they can see the source IP which requested the resource and know when the connection occurred.

With PhishAPI, I took things a step further by automating the XML creation for new documents as well as inserting a hook into existing documents the user can upload through a web interface. This way you should never have to touch the XML or open up a Word document to weaponize it, and everything can be done quickly and easily. I wrote another blog about that process if you’d like to read it. Essentially, PhishAPI works as a web service to listen for these requests and captures IP addresses, user-agent information, credentials (like Phishery, by using basic-auth), and hashes if it’s an SMB request via the UNC call (thanks to Responder in the background!). It does a lot of other things too, such as clones fake portals and creates email templates for campaigns but that’s outside of the scope of this discussion. It then looks up a GUID in a database when it receives a request in order to relate it to a specific phishing campaign and target and then alerts via a specified Slack channel so the “attacker” can be notified in real-time. Enough about PhishAPI though, this is what the XML would look like in the Word document if you were to do something like this manually:

To mitigate this, Microsoft added something called “Protected View” to the Office suite back in the 2010 version. Everyone’s probably familiar with this little yellow ribbon at the top of your documents which you have to “Enable” in order to make changes or run dynamic content. This is Microsoft’s way of protecting the average user who just wants to view a remote document without needing to run macros and other dynamic/remote content. There’s actually a flag that gets set when the document originates from somewhere other than your workstation which enables Protected View. Once you manually override it once, the flag gets reset and will not prompt again for that document. You’re essentially marking this document as safe and can move on. You can also universally disable the setting in Word but that’s not recommended and isn’t a default, so not many users would be susceptible out of the gate.

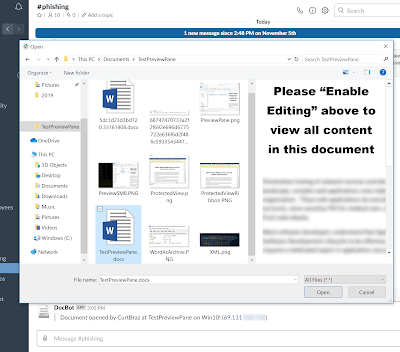

If you don’t supply your own document to PhishAPI, it uses this as a default template in an attempt to fool users into “Enable Editing” on their own. I know, dirty! I borrowed this technique from somewhere else. However, if they just view the document and do not bypass Protected View on their own, the call will never make it to the PhishAPI server and I won’t receive any notification the user even opened it. Bummer!

The Discovery

I used PhishAPI to generate a new document using the default template as I had done many times before. This was for a current social engineering engagement we were performing for a client. I downloaded the Word doc, browsed out to the location using Windows File Explorer, and sent it to a co-worker so they could have some Phishing fun in our Slack channel. I was surprised to see the document had already fired off an alert, knowing that this was a newly created document from the Internet and would have had the Protected View flag still set. I never opened it!

I quickly realized this occurred due to my use of the “Preview Pane” in file explorer on Windows 10. Just highlighting the document caused the internal payload to execute in the context of my user account on Windows. With it being a “preview”, there was no “Protected View” ribbon to display. This was interesting to me because my assumption was that by default, the preview version of the document (both handled by Microsoft) would have simply not shown dynamic or remote content.

You can see in the above image I still received the Slack notification even though this document has yet to be opened. It did not clear the flag from the document, however, because when I opened it in Word I was still prompted and it did not fire the payload. Protected View simply does not apply when previewing it in File Explorer!

Okay, so HTTP requests are one thing, but can SMB requests initiated from UNC calls still leak an NTLMv2 hash from my user account? You bet! I fired up a local instance of Responder to listen on TCP 445/139 and even though “Protected View” was still set, I received my own hash on the local network. Yikes!

To be thorough, I also tested Macros within Excel to see if the same is true, but it seems to be protected. You can preview older “.xls” files but the macros will not fire by default. You have to still “Enable Macros” from the ribbon for those to execute. I tested it myself in the same way with a local Responder instance just to be sure:

Lastly, another thing I noticed is that O365 for web (in a web browser) renders the page without protected view as well and causes (at least) the HTTP payload to fire. This is nice if your target is using O365 and you want to collect those Phishing statistics and know if they opened your email. During my research, I wasn’t able to get SMB to fire in the same way that this bypass technique works. I also noticed the PhishAPI/Phishery plain-text credential technique does not work here or locally due to the preview functionality not prompting for basic-auth when responding to 401 status codes.

So preview pane might not always be enabled on your victim’s workstation, but that’s okay! I’ve noticed the major web browsers (at least Firefox and Chrome) enable previews by default when you’re uploading a file to a web site. The following screenshots are after I disabled Preview Pane in File Explorer and uploaded a file via Firefox and Chrome (Slack). You can see the call in the background of the second image.

Conclusion

So what’s the big deal? Well, for one, if you were crafty with your phishing campaign and you wanted to gather leaked information and hashes, you could probably prompt for an upload on your site to trigger the payload, for example. For another, there’s a big false sense of security users have when dealing with maldocs. They assume as long as they don’t open the file, or they open it but do not accept any prompts, they’re completely safe. However, as I’ve just demonstrated, just having the file exist on their file system is likely to eventually be triggered when the victim is browsing files at a later time. Perhaps they want to select it to send it to the Recycling Bin. This likely explains why a number of my phishing campaigns did not trigger initially but did several months after the campaign had ended, resulting in crackable NTLMv2 hashes.

I’ve sent this to Microsoft’s MSRC team as a potential bypass technique for Office’s “Protected View”. Unfortunately, after a couple of weeks of waiting for a response, they acknowledged this is in fact an issue they plan to address in the future but will not be awarding me with a bounty and plan to offer no future updates. That’s bad news for me, but great news for anyone who plans to leverage this for red teams since there’s unlikely to be a fix anytime soon. Here’s the quote:

“Our engineering team(s) determined that a fix for this issue does not meet our criteria for immediate security servicing. However it is a candidate for consideration for potential improvements in a future version of this product or service. At this time, we will not be providing ongoing updates of the status, or if there will be a fix for this issue, and we have closed this case.

Your report is not acknowledged as a security vulnerability by Microsoft. While all security vulnerabilities are bugs not all bugs are security vulnerabilities that meet the criteria for immediate security servicing.”

Although it doesn’t entirely bypass the security feature within the suite itself, I think there’s still an issue here that exposes users to the risk of stolen credentials or leaked sensitive information at the very least. In fact, I believe it’s more severe than a direct bypass since you don’t even have to open the file, you just have to simply select it. I hope this blog helps to highlight this risk as a user and gives white-hat red teams another vector when Phishing. Hopefully, it will be resolved as I do believe the default should be to not render dynamic or external content. Stay safe out there!